How Long Does California's Autistic Services For Children Last?

Executive Summary

California Serves More than Than xl,000 Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. In 2015‑xvi, California provided early intervention services to almost 41,000 infants and toddlers with special needs. These infants and toddlers either have a disability (such as a visual or hearing harm) or a significant developmental delay (such as not beginning to speak or walk when expected). The country'southward early intervention system provides these infants and toddlers with services such as speech therapy and home visits focused on helping parents promote their child'south development. Parts of California's early intervention system appointment dorsum more than 35 years. During this time, the state has not regularly, or fifty-fifty periodically, evaluated this organisation. In this report, we provide a comprehensive assessment of the system.

Background

Services Are Provided Through Three Programs. California's plan for serving infants and toddlers with special needs involves three programs operated past two types of local agencies.

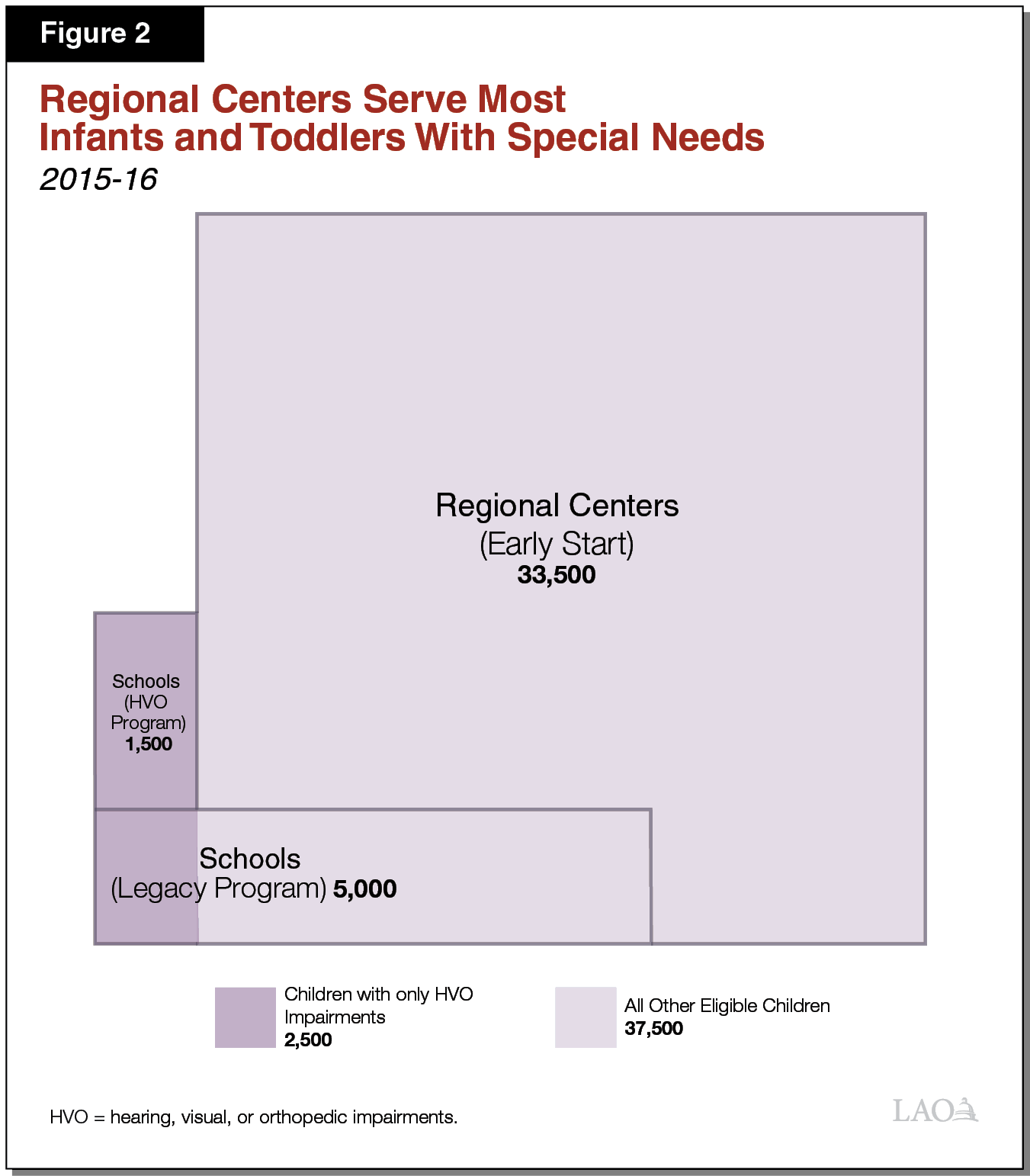

- Regional Centers' Early Start Program. Regional centers are the main provider of early intervention services in California. These centers are nonprofit agencies overseen by the Department of Developmental Services. In addition to their original mission—analogous customs‑based services for adults and schoolhouse‑anile children with developmental disabilities—regional centers coordinate services for about 33,500 infants and toddlers with special needs.

- Schools' Legacy Program. The state also provides early on intervention funding for 97 schools that have a long legacy of providing early on intervention services. The country funds these schools to serve the same number of infants and toddlers equally they served when they starting time received country funding back in the 1980s—almost v,000.

- Schools' Hearing, Visual, and Orthopedic Impairments (HVO) Program. Although regional centers are required to serve most infants and toddlers not served in the school legacy program, schools are required to serve infants and toddlers who have solely HVO impairments and no other eligible condition. Schools currently serve about 2,500 infants and toddlers with HVO impairments, of which most 1,500 are served in the school HVO program and 1,000 are served in the legacy programme.

Country Provides Most Funding for Early Intervention Services. Although services are required as a condition for receiving a federal early intervention grant, this grant covers a relatively small portion (virtually $50 chiliadillion, or 10 percent) of associated service costs. State funding covers the bulk of service costs (about $370 thouillion, or 77 percent), with other fund sources (such as health insurance billing) covering the remainder of costs (about $sixty million, or xiii percent).

Schools and Regional Centers Provide Similar Services Using Different Delivery Models. Although federal police force outlines a general process both schools and regional centers must follow in serving infants and toddlers with special needs, the two types of agencies use notably different service delivery models. Specifically, schools tend to employ their ain service providers (such as speech therapists), whereas regional centers coordinate services offered past independent service providers.

Assessment

Important Differences Between Schools and Regional Centers. Although considerable overlap likely exists in the populations served past the 2 types of agencies, schools spend much more per child than regional centers (almost $xvi,000 every bit compared to nigh $10,000). Additionally, regional centers tend to offer parents more than choice among service providers. Finally, regional centers are better equipped to aid parents access public or private insurance coverage.

California's Bifurcated Organization Probable Causes Service Delays. Because California's system is divided between three programs and two types of agencies, parents and agency staff are frequently confused as to which plan is responsible for serving each kid. Moreover, California lags nearly all states in providing timely services. Many infants and toddlers wait weeks or even months earlier being placed in the appropriate program, during which time they do non receive services. California also performs worse than other states in facilitating transition from early intervention services to preschool special education. Based upon our conversations with stakeholders, we believe these preschool delays likely consequence from some regional centers struggling to coordinate with schools.

Recommendations

Unify All Services Nether Regional Centers. Given the shortcomings of California's bifurcated system, nosotros recommend the land unify the arrangement under ane lead agency. Compared to California's existing system, a unified arrangement likely would provide more than timely services and provide more than equal funding for each child served. Given how the land'due south early intervention organisation has evolved over the past 35 years, we believe regional centers currently are better positioned than schools to serve in this lead capacity. Specifically, regional centers already serve the vast majority of infants and toddlers with special needs, provide more parental option, and are meliorate equipped to access public and private insurance billing.

Establish a Transition Program. Nosotros recommend the state develop a plan to help ensure continuity of services for families during the transition to a unified organization. As part of the transition plan, we recommend the state let regional centers some flexibility in contracting with schools to go on serving some infants and toddlers. We also recommend the regional centers develop transition plans for serving infants and toddlers who are deafened or hard of hearing. In addition, nosotros recommend the state require regional centers to follow established best practices to ensure polish transitions to preschool.

New Organization Would Produce State Savings. Though nosotros recommend transitioning to a new system for the direct benefits it would have for infants and toddlers with special needs, a unified system nether the regional centers also would generate land savings. We approximate savings in the range of $5 chiliadillion to $35 thouillion. The state could repurpose these savings for whatsoever budget priority or apply them to expand or enhance early intervention services (for example, by conducting more outreach or raising associated reimbursement rates).

Introduction

In 2015‑sixteen, California provided early intervention services to about 41,000 infants and toddlers with special needs. These infants and toddlers either have a disability (such as a visual or hearing impairment) or a meaning developmental filibuster (such as not get-go to speak or walk when expected). California's early intervention system consists of 3 programs administered by ii types of local agencies—schools and regional centers for persons with developmental disabilities. This report provides the first comprehensive analysis of this system since it was established in 1993. The report has three primary sections. We kickoff provide background on California's early on intervention system, then assess this organisation, and conclude past recommending several ways to ameliorate the system.

Background

Below, nosotros describe the history of early intervention programs in California, the state's current approach to placing infants and toddlers into each of its three programs, what types of services these iii programs provide, and how these programs are funded.

Origins of System

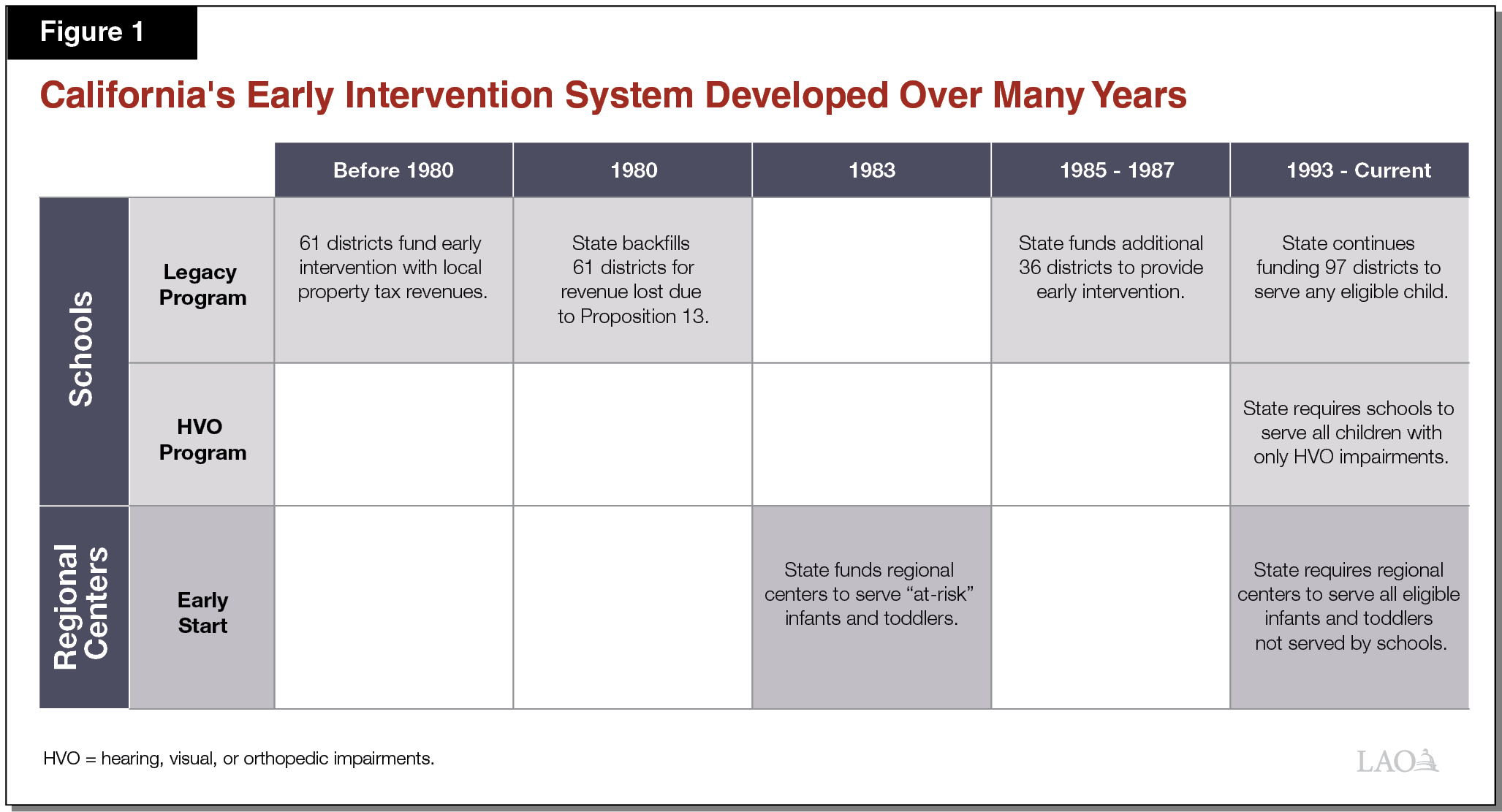

Some Schools Have a Long Legacy of Serving Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. Immediately prior to Proposition thirteen (1978), 61 schools were providing services to a small number of infants and toddlers with special needs. (Throughout this paper, nosotros use the term "schools" to refer to both school districts and county offices of education. "Infants and toddlers" refer to children from nativity until their third birthday.) These 61 programs were funded by local property tax revenue and established at the discretion of local school administrators. Following the passage of Suggestion 13, schools across the state experienced pregnant reductions in property tax acquirement and began eliminating some locally funded programs. To backfill for lost property tax acquirement, California in 1980 began providing state funding to the 61 schools already operating early intervention programs. Between 1985 and 1987, California expanded this land funding to an additional 36 schools. The state continues to fund these 97 schools for serving the same number of infants and toddlers they each served when they outset received state funding—a total of about 5,000 infants and toddlers statewide. We refer to this land funding for these 97 schools as the schoolhouse "legacy program" throughout the residue of this written report.

Regional Centers Likewise Take a Long History of Serving Some Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. In 1965, the state began developing a network of regional centers to coordinate services for individuals with developmental disabilities. The centers—nonprofit agencies overseen by the Department of Developmental Services (DDS)—were designed every bit a community‑based alternative to land institutions. Originally serving adults and school‑aged children with developmental disabilities, regional centers began receiving land funding in 1983 to serve infants and toddlers deemed "at hazard" of condign lifelong consumers of community‑based services. Throughout the 1980s, the state provided several rounds of i‑time funding to expand these early intervention services. By 1988, regional centers were serving about 6,000 infants and toddlers per year.

In 1993, the Country Developed a Program to Serve All Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. Starting in the mid‑1980s, the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Human action (IDEA) authorized annual grants to states that agreed to identify and serve all infants and toddlers with special needs. California was the final state to apply for this federal plan (now known equally Idea Part C), submitting a comprehensive early on intervention plan in 1993. Relative to California's early on intervention programs before 1993, this comprehensive plan significantly expanded the office of regional centers but required all schools to serve infants and toddlers who had merely a hearing, visual, or orthopedic (HVO) damage. In the outset year nether this comprehensive plan, regional centers served virtually eleven,000 infants and toddlers with special needs, compared to 6,000 infants and toddlers existence served by schools (5,000 in the legacy program and 1,000 in the new HVO program).

Current Organisation

Under State's Plan, Regional Centers Serve Most Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. Since 1993, California'south early intervention plan has made regional centers the default agency for serving most infants and toddlers with special needs. In 2015‑16, the state's 21 regional centers served about 33,500 (82 percent) of the 41,000 infants and toddlers receiving early on intervention. Nigh infants and toddlers served by regional centers accept developmental delays, meaning they are significantly backside virtually children in developing of import abilities such every bit speech or motor skills. A smaller number of infants and toddlers served by regional centers accept disabilities such as autism or Down's syndrome. The regional centers' early intervention programme is called Early on Get-go.

Infants and Toddlers With Just HVO Impairments Are Served by Schools. Although California requires schools to serve infants and toddlers who have just HVO impairments, information technology does not require schools to serve infants and toddlers who have HVO impairments in combination with whatever other eligible status. For case, the state requires schools to serve infants and toddlers who are deaf and have no other eligible status but requires regional centers to serve infants and toddlers who are both deaf and take a developmental filibuster. Near 25 years later the land adult its early intervention system, the original rationale for this sectionalisation of responsibilities is somewhat unclear. In conversations with stakeholders, we heard many suggest that schools have a long history of serving older children with HVO impairments and thus were well positioned in 1993 to serve infants and toddlers with like impairments. Schools currently serve virtually ii,500 infants and toddlers with only HVO impairments, comprising 8 percent of all infants and toddlers receiving early intervention services. Nigh 1,000 of these 2,500 infants and toddlers are served in the school legacy plan, whereas the other 1,500 are served in the school HVO plan.

Schools in the Legacy Program Continue to Serve Any Eligible Child. The land continues to fund the 97 schools that have a long legacy of serving infants and toddlers with special needs. Schools in this legacy plan tin serve any eligible infant or toddler and must serve at to the lowest degree equally many infants and toddlers as they served in the mid‑1980s (5,000, or 12 percent of all existing infants and toddlers receiving early intervention services). In 2015‑xvi, in addition to serving approximately 1,000 infants and toddlers with only HVO impairments, the legacy plan served 4,000 infants and toddlers with other disabilities. Effigy 1 summarizes the history of California's 3 early intervention programs, and Figure 2 illustrates the relative proportions of infants and toddlers currently served in each program.

Schools and Regional Centers Use the Same Process to Develop Private Service Plans. Both schools and regional centers follow a five‑step procedure outlined in federal law for serving infants and toddlers.

- Referral. Infants and toddlers typically are referred to a school or regional center by master care physicians following routine check‑ups.

- Evaluation. Following each referral, school or regional centre staff evaluate the kid to determine eligibility for early on intervention.

- Individualized Family Service Plan. For each child deemed eligible for services, his or her family meets with staff to develop an individualized family service programme. These plans are reviewed at to the lowest degree once every six months. Typically, these plans include targeted services like weekly speech therapy sessions and regular home visits from an early teaching specialist who provides support on a wide range of developmental issues.

- Identification of Providers. Staff identify appropriate providers for the services listed in the program.

- Service Provision. Directly service providers travel to each child's dwelling whenever possible, generally providing services alongside the child's parents (or other main caregiver). This final requirement is intended to ensure parents acquire how to promote their child'southward development equally part of their daily routines.

Schools and Regional Centers Use Different Service Delivery Models. Schools typically employ their own early intervention service providers (such as voice communication therapists), whereas regional centers coordinate services from contained providers. Before direct paying for services, regional centers are required by law to showtime access services paid for past families' wellness insurance plans, including Medi‑Cal and private insurance. Regional center service coordinators typically help families navigate the health insurance organisation to get early intervention services covered. When a family's insurance network does not provide piece of cake admission to a specified early intervention provider (as is oft the case), regional centers pay for these services with country funding.

In Some Cases, Schools Provide Services Nether Regional Heart Contracts. Regional centers tin can contract with any qualified provider of early intervention services. Typically, these providers are either nonprofit organizations specializing in early intervention or independent clinics offering oral communication therapy, physical therapy, or other specialized services. Regional centers also sometimes contract with schools to provide early intervention services. These schools typically provide the aforementioned services to infants and toddlers served under regional center contracts as they provide to infants and toddlers served in the legacy program. In 2015‑16, regional centers contracted with a total of eighteen schools to provide $xiii thousandillion of early intervention services.

Federal Law Requires Administering Agencies to Initiate Services Presently Afterward Referral. Under Idea, schools and regional centers must develop an initial individualized family service programme no subsequently than 45 days after each child'due south referral. They must begin services no afterwards than 45 days after development of the initial service plan. These requirements are intended to ensure eligible children do not fall even further behind their peers while waiting to receive early intervention. All states must annually written report their compliance with these deadlines to the federal government, which uses such data to evaluate the performance of each state'south early on intervention system.

Some Children Transition to Preschool Special Educational activity Upon Turning Iii. Many children receiving early intervention bear witness meaning progress and are determined to no longer require special supports at age three. For example, some infants who accept not spoken their first words by 18 months and are diagnosed with initial communication delays overcome those issues by age three. Some three year olds, nonetheless, have more serious and lingering disabilities (such as visual impairments or autism). About 45 percent of children served by California's early intervention system qualify for special instruction at historic period 3. To ensure a seamless transition from early intervention to preschool services, the federal government requires early intervention providers to piece of work with each kid'south school to develop a transition plan no afterward than 90 days before his or her third birthday. As with the deadlines for initial service delivery, all states must annually report their compliance with this transition deadline.

Some Children Become Lifelong Consumers of Regional Center Services. At age three, regional centers assess children to determine if they are eligible for ongoing services through DDS (unless parents practise non want their child assessed). To be eligible, children must have a developmental disability that is substantial in nature and expected to go along indefinitely. Qualifying disabilities are autism, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, or other disabling status like to intellectual disability or that requires like treatment. Statewide data show near 20 percent of children who receive early intervention keep to become agile DDS consumers. (About of these children besides authorize for preschool special didactics.)

Funding

State Funds Most Early Intervention Services. Figure three shows state and federal funding in 2015‑sixteen for early on intervention services in California. Across the three early intervention programs, the land provided $367 million (88 percent), whereas the federal government provided $50 one thousandillion (12 percent).

Figure 3

State Funds Most Early on Intervention Services a

L AO Estimates for 2015‑16 (In Millions)

| Program | Amount |

| Regional Centers: Early Start | |

| State Not‑Proposition 98 General Fund | $289.8 |

| Federal Thought Function C Grant | 35.ix |

| Subtotal | ($325.7) |

| Schools: Legacy Plan | |

| State Proffer 98 General Fund | $74.eight |

| Subtotal | ($74.8) |

| Schools: HVO Program | |

| Federal IDEA Part C Grant | $fourteen.2 |

| State Proffer 98 General Fund | ii.4 |

| Subtotal | ($xvi.vi) |

| Total | $417.1 |

| aDoes non include (1) Early on Kickoff services billed to Medi‑Cal and private insurance; (2) Early on Start services reimbursed past federal Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Handling funding; or (3) general purpose Chiliad‑12 funds locally repurposed to back up school‑based early intervention. HVO = hearing, visual, or orthopedic impairments and IDEA = Individuals with Disabilities Teaching Act. | |

Most Early on Start Provider Rates Are Determined by State Policy. Prior to 2003, DDS gear up a range of allowable rates for providers of most Early Commencement services. Within the allowable range, regional centers prepare a specific provider'due south rate based on that provider's documented costs. (Although schools providing Early Showtime services under regional middle contracts were not discipline to these allowable ranges, their rates were similarly based on each school's documented costs.) Starting in 2003, the Legislature effectively froze rates for existing providers and capped rates for new providers at the statewide average rate for existing providers. Since 2003, virtually Early Start charge per unit increases accept been due to increases in the statewide minimum wage. These rate policies practice not apply to speech, physical, or occupational therapists, each of which receive a uniform statewide rate equal to the Medi‑Cal rate for such services. Since 2003, Medi‑Cal rates for these types of therapists have been largely unchanged.

Before Using Early First Funds, Regional Centers Determine if Insurance Coverage Is Available. Country law requires regional centers to assistance families admission services covered past their private or regime‑sponsored health insurance plans earlier using land funding to pay for early intervention services. Despite this requirement, nosotros guess relatively few early intervention services are paid for past insurance. Specifically, we estimate Medi‑Cal provides nigh $40 million annually for early intervention, and individual health insurance provides less than $20 million annually. By comparison, regional centers provide about $325 million annually from country and federal funding for Early First.

State Funds School‑Based Programs Using Two Funding Formulas. As detailed in the nearby box, the state maintains one formula to fund the legacy plan and another to fund the HVO program. Compared to Early Start, neither program receives notable reimbursements from third‑party insurance. Though state police force does non prohibit schools from accessing such funding, bachelor data indicate insurance covers less than 1 percent of schoolhouse‑based early intervention costs.

Funding for Schoolhouse Programs

Legacy Programme Funded Through Complicated Formula. Since 1980, schools in the legacy programme have been funded using a formula originally developed for K‑12 special instruction. The formula is linked to the estimated cost of specific K‑12 special education services. For example, schools receive one charge per unit for special day classrooms serving only students with special needs and some other rate for serving students with special needs in mainstream classrooms. Each district receives a unique charge per unit per special didactics service based on a statewide survey of special education costs conducted in 1979‑lxxx, with cost‑of‑living adjustments. Importantly, the country no longer uses this formula to fund K‑12 special didactics, having adopted a simpler and more flexible funding formula in 1998. Though the state continues to use the more than dated and complicated formula to fund early intervention, stakeholders accept long argued the formula is a poor proxy for the price of these services. More than than xxx years have passed and the formula remains unaltered.

HVO Programme Has Been Flat‑Funded for Two Decades. School hearing, visual, or orthopedic (HVO) programs have received no funding increases since 1996‑97. Rather, country and federal funding has remained abiding at $16.vi thousandillion even as the total number of infants and toddlers with only HVO impairments has increased from about one,500 in 1996‑97 to about ii,500 today. Because state and federal funding has non kept pace with increasing service costs, HVO programs probable rely more than heavily on locally repurposed K‑12 funding than legacy programs.

Schools Supplement Early on Intervention Funding With Locally Repurposed M‑12 Funding. School expenditure data testify that state and federal early on intervention funding is insufficient to cover the total cost of school‑based programs. Consequently, schools cover some early on intervention costs with a combination of K‑12 general education funding (mostly from the Local Control Funding Formula) and K‑12 special education funding. Nosotros estimate schools embrace between $five million and $10 million annually in early intervention costs with repurposed Yard‑12 funding.

Assessment

Beneath, we compare the programs run by schools and regional centers, assess the timeliness of service planning and commitment, and examine how smooth the transition is from early intervention services to preschool special education services.

Comparing the Two Types of Agencies

Likely Considerable Overlap in Populations Served past Schools and Regional Centers. In theory, the country intended schools to serve generally infants and toddlers with HVO impairments, whereas regional centers would serve virtually other types of infants and toddlers. In practice, nosotros think the populations served by each agency overlap notably. Specifically, based on available school information, we extrapolate that regional centers serve every bit many every bit 45 percent of all infants and toddlers with HVO impairments. Regional centers likely serve such a loftier share of these children because the state plan requires them to serve infants and toddlers who take HVO impairments in combination with whatsoever other eligible condition. At the aforementioned fourth dimension, considering schools in the legacy plan can serve any eligible child, statewide school data indicate nearly lx percent of all infants and toddlers served past schools practice not take HVO impairments. Though we doubtable considerable overlap in the types of children served by regional centers and schools, the regional centers do non compile data on infants and toddlers served past type of disability. Due to this data limitation, whether regional centers, on average, have more or less severe caseload is unknown.

Regional Centers Provide Same Types of Services at Much Lower Cost. To help appraise relative toll‑effectiveness, we compared the per‑child expenditures on early intervention services at schools and regional centers in 2015‑16. After accounting for all fund sources, we estimate schools spent threescore percent more than regional centers per child served. Specifically, nosotros estimate schools spent well-nigh $16,000 per child whereas regional centers spent nearly $10,000 per child. Based on conversations with local stakeholders and a review of the available data, we believe at least two factors contribute to this large cost difference. First, schools typically pay service providers for travel fourth dimension and cancelled appointments whereas regional centers exercise non. 2nd, schools are more likely to provide services through credentialed teachers, who tend to be better compensated than other early education specialists. The bachelor data exercise not allow us to make up one's mind what share, if any, of the cost difference is due to schools possibly serving infants and toddlers with more than severe disabilities. Comparative data on the number of services provided per kid are also unavailable, so nosotros could non determine the extent to which that factor might be driving toll differences.

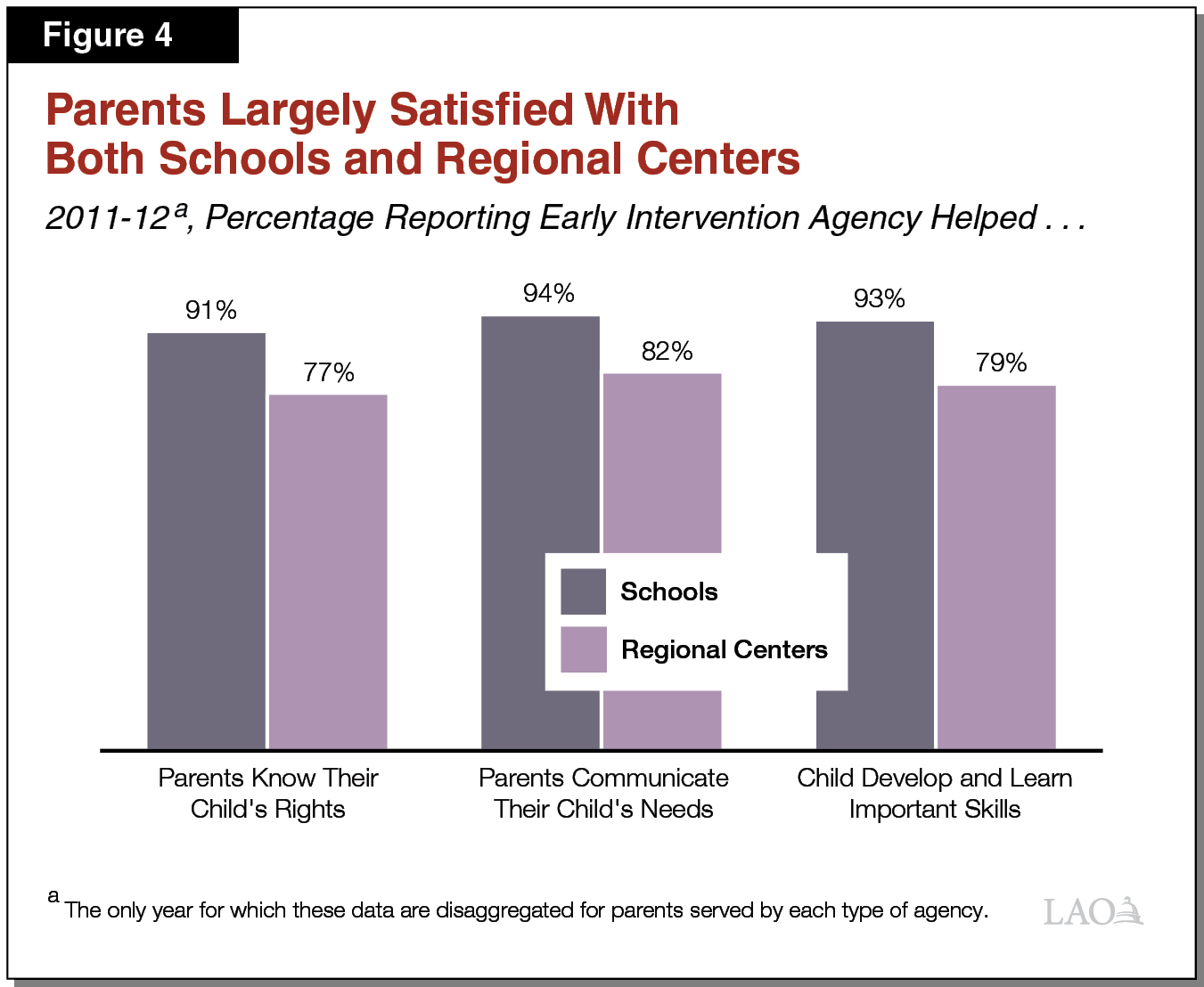

Parents Largely Satisfied With Both Agencies. Figure 4 shows the results of a parental satisfaction survey conducted in 2011‑12. Large majorities of parents reported being satisfied along iii dissimilar service dimensions, regardless of which agency served them. A somewhat larger share of parents served past schools, however, expressed satisfaction than those served by regional centers.

Regional Centers Offer More Parental Choice Than Schools. Parents served in school programs typically cannot choose their early on intervention service providers. They must accept services from the schoolhouse's own employees. By dissimilarity, parents served by regional centers often have a choice of several providers. This could be one reason parents served by regional centers are nearly as satisfied with their services as parents served by schools, despite schools spending notably more per child.

Regional Centers Are Better Equipped to Help Parents Access Medi‑Cal and Private Insurance. Parents served past schools rarely bill Medi‑Cal and well-nigh never bill individual insurance for early on intervention, meaning the land must pick up almost the entire price of school‑based programs. By comparison, regional centers are more accepted to working with families to admission third‑political party insurers, which produces state savings.

Service Deadlines

Timely Service Commitment Is Crucial in Early Intervention. Children develop quickly during their starting time three years, such that babies developing just a few days behind their peers can quickly grow into toddlers several months or fifty-fifty a yr behind. Concerned that such widening gaps might result in long‑run academic challenges, the federal government sets deadlines for providing early on intervention services.

California's Bifurcated System Probable Causes Service Delays. Families and early intervention staff often accept difficulty determining whether schools or regional centers are responsible for serving a particular infant or toddler. For example, a toddler who is orthopedically impaired will typically be served in the school HVO program, unless he or she also has a developmental filibuster, in which case he or she will typically exist served by a regional center. However, if this toddler resides near a school receiving legacy program funding, he or she typically receives school services, unless the schoolhouse has already filled its legacy program capacity, in which instance he or she can only be served by a regional center. Determining an infant or toddler's placement tin can sometimes take days or even weeks, thereby delaying services.

California Lags Other States in Providing Timely Services. Effigy 5 compares California's operation in meeting federal early intervention service deadlines with other states. Though near states comply with these deadlines more than 95 percent of the time, California complies less than 85 percent of the time. Ane of the few states to perform worse than California on these measures, South Carolina, is also the only other state we could identify that divides its early intervention system betwixt 2 state agencies. (South Carolina ranks final nationally in meeting both deadlines.)

Figure 5

California Does Poorly in Meeting Federal Deadlines

Percent of Children for Which State Completed Activities on Time, 2013‑14 a

| Develop Initial Service Plan | Begin Services | |

| 25 thursday ranked land | 97.9% | 98.3% |

| 40 th ranked country | 95.1 | 94.6 |

| California b | 82.1 | 82.1 |

| aAn initial service programme is to be developed within 45 days of referral. Services are to begin within 45 days of developing an initial service plan. bCalifornia ranks 46thursday amidst the 50 states in coming together the initial service plan deadline and 47th in meeting the begin services borderline. | ||

Preschool Transition

California Performs Worse Than Other States in Facilitating Transition to Preschool. Figure half dozen compares California's performance to that of other states with regard to meeting federal deadlines for transitioning children from early intervention to preschool special education. Every bit with the deadlines for initial service delivery, California lags behind the large majority of states at key transition phases. In particular, California lags far behind other states in notifying schools of children who are receiving early on intervention services and soon to turn three. When schools are not notified ahead of time, they cannot participate in developing transition plans (which are then developed solely past the regional centers), likely resulting in less seamless transitions.

Effigy 6

California Does Poorly in Planning Preschool Transitions

Percentage of Children for Which State Completed Activities on Time, 2013‑14 a

| Notify School | Hold Planning Briefing | Develop Transition Programme | |

| 25 th ranked state | 99.seven% | 98.0% | 99.3% |

| forty th ranked land | 94.3 | 90.7 | 94.four |

| California b | 74.v | 86.two | 91.iv |

| aDeadline for all activities is 90 days earlier child's third altogether. bCalifornia ranked 47th among the 50 states in notifying schools virtually impending transitions, 44thursday in holding planning conferences, and 47th in developing transition plans. | |||

Transition Challenges Likely Due to Poor Regional Middle Practices . Unlike with early intervention, agencies have no defoliation over who is responsible for serving children in preschool special teaching—schools e'er have this responsibleness. Consequently, regional centers must coordinate with schools to ensure a smooth transition. Many stakeholders indicate regional centers practise not always follow best practices in coordinating these transitions, which probable explains California'south weak results relative to other states in meeting federal deadlines.

Recommendations

Below, we make a series of recommendations that if taken together would substantially accost the concerns highlighted in the previous section. Showtime, we recommend unifying the country'due south early intervention system under a single agency. Second, we recommend the state make several changes to ensure a smooth transition to a unified system. Finally, considering we anticipate the new arrangement would result in state savings, we briefly discuss options for using these savings to either expand or meliorate early intervention.

Unify System

Unify Organisation Under a Unmarried Agency. We recommend shifting all major program responsibilities (along with all country and federal early intervention funding) to a unmarried bureau. Nosotros believe such a unified system would provide families more timely services. A unified organization as well would simplify state funding allocations and eliminate the current funding differences among the land'southward three early intervention programs. Additionally, a unified organisation could offer some families more choice among service providers.

Make Regional Centers Responsible for Serving All Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. Given how California's organisation has evolved over the years, we believe regional centers currently are better positioned than schools to run an early intervention organization. Regional centers already serve the vast majority of infants and toddlers with special needs. Whereas shifting the approximately half dozen,500 infants and toddlers currently served by schools to regional centers would increase the regional heart Early Start caseload by 19 percent, shifting the approximately 33,500 infants and toddlers served by regional centers to schools would increment the school early on intervention caseload past more than 500 percent. Considering schools spend notably more than regional centers per child served, shifting all infants and toddlers from schools to regional centers as well likely would produce state savings. By dissimilarity, we estimate information technology could cost as much equally $200 million to shift all infants and toddlers from regional centers to schools. Finally, we believe the state can go on to enjoy the benefits of schoolhouse‑based programs (for example, expertise in serving children with HVO impairments) even afterwards shifting all infants and toddlers to regional centers by encouraging more than schools to provide services nether regional center contracts. Shifting all infants and toddlers to schools, however, probable would undermine the existing benefits of regional center programs, including greater parental choice and 3rd‑political party billing.

Establish Transition Plan

Encourage Schools to Continue Serving Infants and Toddlers Under Regional Center Contracts. Although we believe regional centers mostly are better positioned to oversee a unified early intervention system, schools currently are the only early on intervention providers in some rural counties. Moreover, schools tend to have more than expertise in serving children with HVO impairments than other providers. To ensure infants and toddlers who live in rural areas or have HVO impairments continue to receive services, nosotros recommend requiring regional centers during the transition period to contract with schools that currently participate in the legacy and HVO school programs. We further recommend funding regional centers such that they can negotiate higher reimbursement rates for these schools during the transition, as these schools currently receive funding rates that are higher than regional center rates. In the long run, however, we recommend any further rate increases apply every bit to both schools and other types of Early Beginning providers.

Require Regional Centers to Develop Transition Plans for Serving Infants and Toddlers Who Are Deafened or Difficult of Hearing. Among disabilities and developmental delays, deafened or hard of hearing seems to arouse the greatest policy controversy regarding appropriate early intervention services. In response to potential concerns about how deafened or hard of hearing infants and toddlers may fare nether a unified system, we recommend the Legislature require regional centers to develop specific transition plans for this group. Specifically, we recommend these regional center plans specify the providers they have lined up to serve these children and outline the approach they will apply to ensure each child receives appropriate support. We recommend subjecting these plans to review and approval by the California Section of Education's Function for Deaf and Difficult of Hearing Students. Such an arroyo would leverage the department's existing expertise in serving these children.

Establish Best Practices to Improve Preschool Transition. To improve preschool transitions, nosotros recommend the Legislature adopt statute requiring regional centers to exercise a serial of best practices. These best practices would include having regional centers develop almanac interagency agreements with each school in their service surface area to specify the general process for handling preschool transitions, place a specific point of contact at each school for coordinating all transitions, and implement shared data systems to let both agencies to track children nearing their third birthdays. We believe these recommendations could be accomplished either by reprioritizing existing resources or with a relatively minor increase in regional center funding of no more than $one.5 grandillion.

Repurpose State Savings

Unified System Likely Would Effect in State Savings. Though we recommend transitioning to a unified organisation for the directly benefits it probable would have for infants and toddlers with special needs, such a shift likely also would result in state savings. This is considering regional centers are both ameliorate equipped than schools to aid parents access third‑party insurance coverage and tend to pay less than schools for each kid served. We estimate shifting all infants and toddlers with special needs from schools to regional centers would save the country betwixt $5 1000illion and $35 yardillion annually. The exact savings would depend on many factors, including how many infants and toddlers continue to be served by schools nether relatively generous interim regional center contracts and how many early on intervention therapies are billed to third‑party insurers. (These savings are contingent upon the country removing current funding from the Proposition98 yardinimum guarantee. Precedent exists for rebenching the guarantee in such cases.)

State Could Repurpose Savings to Aggrandize or Better Early Intervention. The Legislature would have many options for repurposing state savings, ranging from redirecting the savings to other parts of the state upkeep to putting the savings dorsum into schools or regional centers. If the Legislature wanted to go along the savings within the area of early intervention, it, in turn, would have many options. For instance, the state could acquit targeted outreach aimed at identifying and serving more infants and toddlers with special needs or it could raise reimbursements rates. Raising rates likely would help retain existing providers in the system and encourage more providers to participate, which, in turn, would increase parental option. The Legislature would face difficult merchandise‑offs equally they weighed these options. For instance, many DDS programs, as well every bit other country programs, want higher reimbursement rates.

Conclusion

California's early on intervention program has notable weaknesses. In detail, its bifurcated design results in service delays and large differences in the amount of funding and parental selection offered to families served past schools and regional centers. We recommend unifying the organization and serving all infants and toddlers through regional centers. We believe this unified system would address the organisation's major weaknesses while generating state savings that could be used to expand or improve early intervention services.

How Long Does California's Autistic Services For Children Last?,

Source: https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/3728

Posted by: clarkstideass.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Does California's Autistic Services For Children Last?"

Post a Comment